The Indie Beauty And Wellness Fallout From Silicon Valley Bank’s Collapse

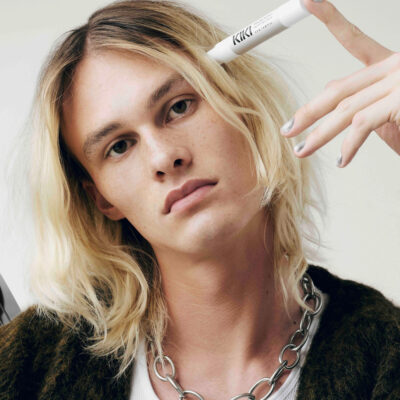

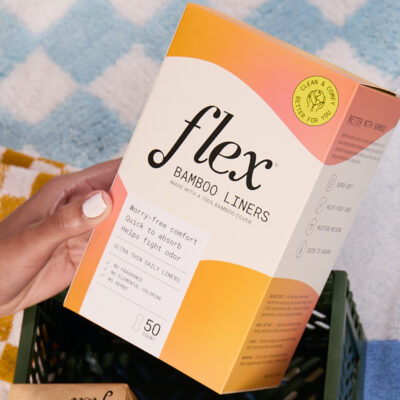

The Flex Company founder Lauren Schulte Wang was manning her brand’s booth at the consumer packaged goods trade show Expo West on Thursday afternoon when she began receiving worrisome texts from fellow founders about Silicon Valley Bank, where The Flex Company did all of its banking.

She recalls, “They were saying, ‘Our investors are telling us to pull all of our money out,’ and I’m like, ‘What are you talking about?’ I start texting our board and investors saying, ‘I’m hearing these rumors, what are you recommending your companies to do?’”

Schulte Wang stepped outside of the Anaheim Convention Center, where Expo West was being held, to suck in a few deep breaths and find out more from The Flex Company’s board members and investors. Most advised her to wait to see what happens before withdrawing the brand’s money from SVB, but she didn’t wait long.

A statement from Y Combinator CEO Gary Tan reminding startups that the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. covers up to $250,000 per depositor prompted her to take action. The Flex Company is backed by Y Combinator.

“He had said, ‘If you’re a company and you go out of business as a result of a bank run, anything over $250,000 in a bank is on you, you’re accountable for it,'” recounts Schulte Wang. “So, we decided to try to withdraw our funds even though we knew that, the more people that do that, if there’s a bank run, that’s a worst-case scenario. It’s a self-fulfilling prophecy.”

Schulte Wang concluded she had no choice but to cut ties with SVB to process payroll by Monday. “If you don’t have the funds for payroll in California you’re criminally liable as an officer of a company,” she says, adding, “We have people with medical bills, we have people with families to feed, mortgages. People are counting on their paychecks coming through. I promised my team that no matter what was happening with Silicon Valley Bank, they would all still be paid on time.”

When news of SVB’s collapse reached New York-based hormone health-focused skincare and supplement brand Veracity Selfcare founder Allie Egan, she was in Los Angeles for work. Similar to The Flex Company, Veracity did all its banking with SVB, taking advantage of a line of credit the bank tailored to early-stage companies. Because Veracity had a line of credit with SVB, which Egan notes it “didn’t draw on, so we had no debt with them,” the company was required to have its money at the bank.

On Friday morning, as SVB’s collapse was making headlines, companies were unable to log onto their accounts at the bank and access their money. Veracity and The Flex Company couldn’t extract their money from SVB.

A number of brands, including Veracity, outdoor skincare specialist Kinfield and Asian seasoning startup Omsom, jumped on social media to update and ask for support from customers, many of whom had never heard of SVB before. Veracity initiated a GoFundMe campaign to raise emergency cash. Egan reports the campaign drew a small amount of money that she plans to pay back in full.

On Saturday, Schulte Wang drove to a local retail bank to open up an account for The Flex Company, and the brand reached out to its retail partners to inform them to send money to the new account. “Even though SVB had collapsed, we could see that our money was still flowing into the bank. We were able to give them our new bank account number,” she says. “Target and Walmart were the first to be really responsive and get things in the right direction for us.”

Schulte Wang transferred her family’s liquid life savings to the new account to ensure there would be sufficient funds to cover payroll for The Flex Company’s 30 employees.

She says, “I am not a wealthy person. When I started the company in 2015, I cashed out my 401k to start my business and to be able to manufacture our first products…A lot of investors were saying, ‘I don’t think that’s a great idea.’ My friends told me not to do it. My parents told me not to do it, but my husband and I honestly felt like, if we were in the same position as our employees, we would want to know that we were getting paid.”

Prior to its collapse, SVB reported almost half of the country’s venture capital-backed technology and life-science companies banked with it along with 2,500 VC firms. The Santa Clara-headquartered bank had $175 billion in deposits, a figure that made it the 16th largest bank in the country, and has become the second-largest bank failure in American history. In The New York Times’ explainer of SVB’s demise, reporter Vivian Giang details that its coffers dwindled as startups suffered in the current economy.

She writes, “The bank also had a significant number of big, uninsured depositors — the kind of investors who tend to withdraw their money during signs of turbulence. To fulfill its customers’ requests, the bank had to sell some of its investments at a steep discount. Once Silicon Valley revealed its huge loss on Wednesday, the tech industry panicked, and start-ups rushed to pull out their money, resulting in a bank run.” A California regulatory agency shut down SBV on Friday, and the federal government subsequently assumed control.

On Sunday, the Federal Reserve and FDIC announced SVB deposits beyond the $250,000 federally insured cap will be guaranteed. Claire Chang, founding partner of San Francisco-based investment firm IgniteXL Ventures, says the guarantee is “a huge relief. Had it not been for this move by the FDIC, emerging brands, many of which work with angels or micro VC funds that lack the ability to step in and offer short-term loans or other means of emergency capital would have been in serious trouble.”

Brands banking with SVB were able to access their accounts Monday, usually after maddening hours of log-in attempts. Kinfield wired funds from SVB to a new account at another bank. Founder Nichole Powell says, “Seeing your bank account go to $0 is a terrifying experience for any business owner, but it forced some thoughtful discussions as a team over the weekend about what we would need to do to survive if we never saw those funds again.”

While Kinfield’s brand’s investors and vendor partners offered to help keep it afloat, the brand will be making changes to its operations to better protect its business in the future. Powell says, “This experience taught me about the existence and value of ‘deposit sweep’ accounts, which is a brilliant way to keep money secured if you’re storing more than $250,000, the FDIC insured limit, with one bank.”

According to Rebecca Lake, a contributor to the Smartasset blog, “A sweep account is a special type of account that can be linked to a bank account or brokerage account. These accounts are designed to maximize funds that may be sitting idly by transferring or ‘sweeping’ them into a higher yield investment option automatically…Transfers may be triggered when funds in your main account are above or below a certain threshold. You may be able to specify what target balance you’d like to maintain and when sweeps should occur.”

SVB’s collapse comes at moment characterized by tight startup funding. Tina Bou-Saba, co-founder and co-managing partner at investment firm Verity Venture Partners, cites “rising interest rates, slowing consumer spending, higher online customer acquisition costs, higher expenses required to succeed at retail and VC lack of interest in consumer now that DTC is not a ‘thing’” as sources of the deal flow slowdown. She believes SVB’s failure will act as an accelerant to the bearish conditions, even though emerging consumer packaged goods brands weren’t a core client group of SVB.

“The indirect results are significant,” says Bou-Saba. “SVB sat at the center of the startup ecosystem, and its failure will leave a huge hole for investors and companies alike, SVB-funded companies that more traditional banks would not touch. This will accelerate the contraction that was already happening in VC, and it’s hard to believe that it won’t hit emerging brands as well. I think that it will continue to be quite challenging for most emerging brands to raise money, especially with consumer spending uncertainty this year, and valuations and round sizes will reflect this, even for those brands that do raise money.”

Chang is optimistic about the long-term funding outlook. Although she points out investors are concentrating on their existing portfolio companies now, she says, “In the long term, investors will resume looking for the next exciting team to back. However, the precarious macro economy remains so the overall focus for founders should be capital efficiency, runway optimization and profitability.”

Odile Roujol, founding partner at investment firm Fab Co-Creation Studio Ventures, argues SVB’s shuttering will cause meaningful losses for the entrepreneurial ecosystem beyond cash flow. She remarks it forged relationships within the startup community.

“They were connecting people, especially founders and investors, organizing events. When I arrived in the San Francisco ecosystem, I didn’t know anybody. The first meeting I had was a Silicon Valley Bank event. They very much believed in the value of relationships in the long term,” she says. “I wouldn’t say that of all banks. That’s a positive thing. Even if it was mismanaged from a financial point of view, that part was very well-managed.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.